Tracking DNS Records in Version Control

This blog post was featured in the NS1 Customer Stories blog

During my first month at Insider Inc, I was given my first real task - figuring out how to track DNS records in version control. The organization has hundreds of DNS records across half a dozen domains and managing them has become cumbersome.

To paraphrase our tech lead, “I don’t want to ever have to see the Dyn console for the rest of my life”

The DNS infrastructure setup was simple enough. Dyn was in use as the primary provider with NS1 as the secondary. If someone wanted to make a DNS change, they would have to log into the Dyn console. Making this change seemed simple enough at first, so I got to work.

Note: More information about the primary-secondary DNS relationship here

First Attempt: The Dyn API

Dyn provided what appeared to be a robust API with great documentation and it even had a Python package, as well.

Unfortunately, actually working with it was less than ideal. I had a lot of trouble making simple requests with the Python package, so I had to resort to making requests using the requests Python package.

data = {

"customer_name": "businessinsider",

"user_name": "mdolah",

"password": "<REDACTED>"

}

headers = {

'Content-type': 'application/json',

'Accept': 'text/plain'

}

r = requests.post('https://api.dynect.net/REST/Session/', data=json.dumps(data), headers=headers)

print(r.content)

The above code instantiated a Dyn Session. With it, I could make requests to update DNS records. Still the API wasn’t the best to work with, so I turned my attention over to NS1.

Second Attempt: NS1 as the Primary

The NS1 API had much better documentation and, even better, included its own up to date Python package. This would require us to migrate NS1 as our primary provider, but this turned out to be a relatively trivial task.

Note: For those unaware, you can use NS1 as the primary provider

The below code is a little proof of concept I quickly scratched together using our test zones in NS1.

#! /usr/bin/env python3

from ns1 import NS1

from pprint import pprint

import yaml

import os

def validate_record(api, zone, records):

print("records")

# pprint(records)

print(records['short_answers'])

zone_api = api.loadZone(zone)

# print("zone API data")

# pprint(zone_api.data)

def main():

path = 'ns1configs/'

for config_file in os.listdir(path):

with open(path + config_file, 'r') as yaml_file:

try:

# pprint(yaml.safe_load(yaml_file))

yaml_data = yaml.safe_load(yaml_file)

except yaml.YAMLError:

print(yaml.YAMLError)

# pprint(yaml_data)

api = NS1(apiKey=os.getenv('NS1_TOKEN'))

zone_records = yaml_data['records']

for record in zone_records:

validate_record(api, yaml_data['zone'], record)

zone = api.loadZone('testbizone.com')

record = zone.loadRecord('apple.testbizone.com', 'A')

pprint(record.data)

record.update(answers=['3.3.3.3']) # Update answers in NS1

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Here’s the general structure for how the project as a whole would work

- The DNS records would be stored in a series of YAML files (one YAML file per domain stored in the

ns1configsdirectory) - Once DNS record was committed, a Jenkins Pipeline would be triggered

- The script would parse the YAML files and detect changes in the record in the YAML file against what NS1 currently had and make the appropriate update

Unfortunately, this proved cumbersome for a few reasons:

- We would need to maintain the Python script as well as the YAML files containing the DNS records

- There are a lot of moving parts and it would be very easy for something like this to break

- The YAML files themselves became a bit too much to handle

For the above reasons, this was shelved in favor of . . .

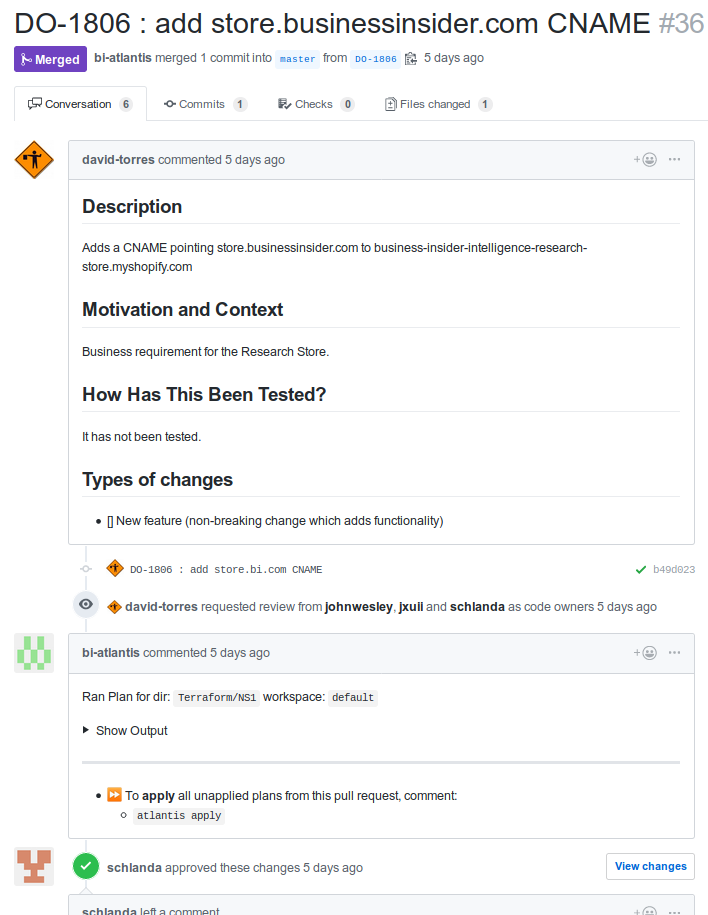

Final Attempt: Terraform!

NS1 offers a Terraform provider!

This solves the above issues by

- Only the Terraform files are need to be maintained (no external script)

- Making DNS updates is as simple as

terraform apply(we use Atlantis internally) - The content of the Terraform files is clearly defined in the documentation

Here is the main zone for businessinsider.com (one zone per Terraform file)

resource "ns1_zone" "businessinsider_com" {

zone = "businessinsider.com"

}

Here is how www.businessinsider.com is defined

resource "ns1_record" "www_businessinsider_com_CNAME" {

zone = "${ns1_zone.businessinsider_com.zone}"

domain = "www.${ns1_zone.businessinsider_com.zone}"

type = "CNAME"

use_client_subnet = "false"

answers {

answer = "f.shared.global.fastly.net."

}

}

The only tricky part with the initial implementation is how to import the existing NS1 domains into the Terraform resources (remember that that we have hundreds of DNS records across almost a dozen domains).

The solution for this was automation! I wrote a Python script import the existing resources into the Terraform state. It automates adding the resources to the Terraform files, too

The script can be found in this gist

Conclusion

While the initial implementations weren’t ideal, I think it’s difficult to argue with the end result Updating DNS records has gotten so easy, that even individuals on different teams have gotten in on it